From Morris to Material Design

How the Arts and Crafts Movement Shaped Digital Product Design

How the Arts and Crafts Movement Shaped Digital Product Design

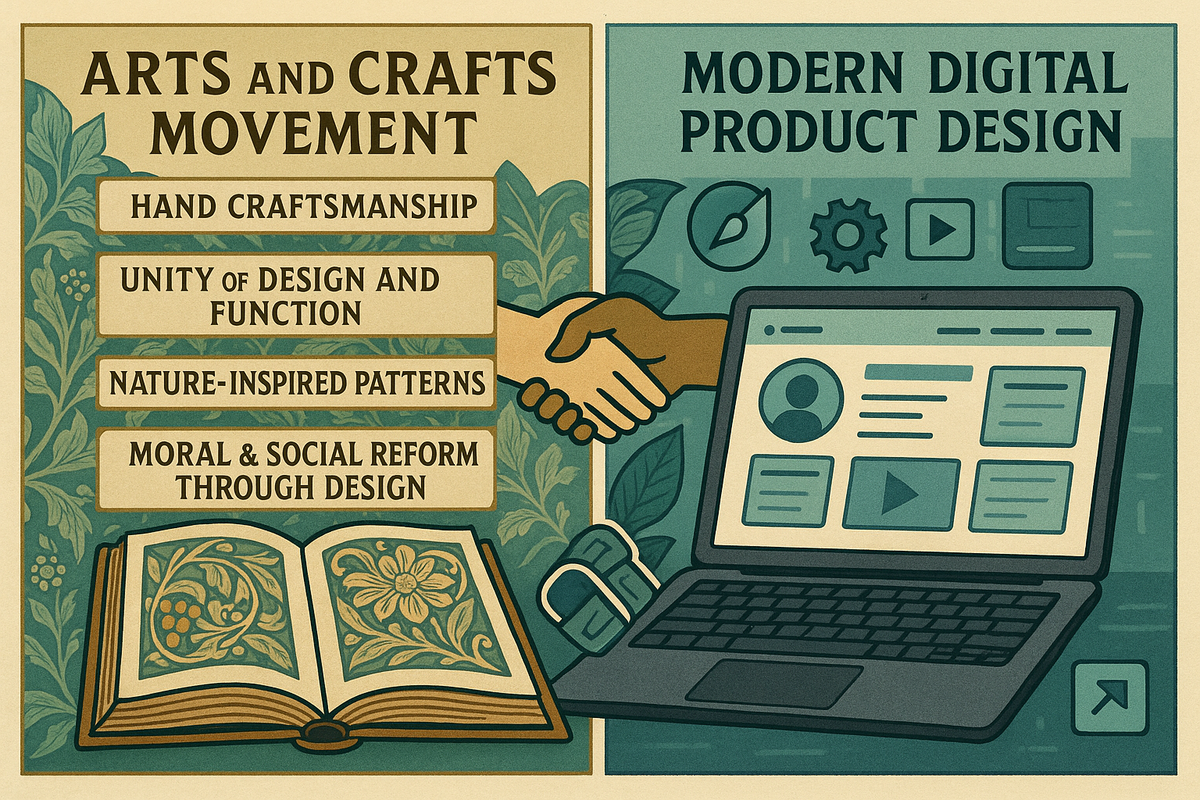

There’s something beautifully ironic about finding 19th-century craftsmanship principles embedded in the sleek interfaces of our smartphones. When William Morris proclaimed “have nothing in your house that is not useful or beautiful” in 1882, he couldn’t have imagined his philosophy would one day guide the design of apps used by billions. Yet the DNA of the Arts and Crafts movement runs deep through modern digital product design, influencing everything from Google’s Material Design to Apple’s relentless pursuit of simplicity.

The Arts and Crafts movement, which flourished from 1880 to 1920, emerged as a reaction to the ornate excesses of Victorian design and the dehumanizing effects of industrial mass production. Led by figures like William Morris and later, Gustav Stickley, the movement championed natural materials, functional beauty, and democratic access to good design. These principles, revolutionary in their time, have found new life in the digital age.

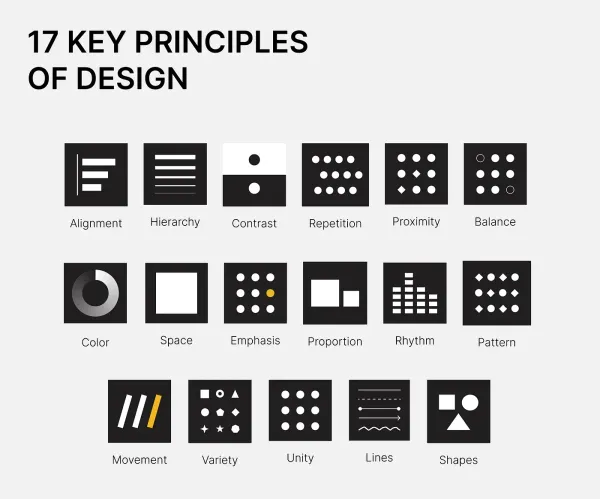

The Timeless Principles

Truth to Materials was perhaps the movement’s most radical idea. Arts and Crafts designers celebrated the natural grain of wood instead of painting it to look like marble, and embraced the natural properties of clay rather than forcing it into unnatural forms. This honest approach to materials translates directly into digital design’s evolution from skeuomorphism to flat design.

Remember when iOS icons looked like leather-bound books and trash cans? That was digital design lying about its materials, pretending pixels were physical objects. The shift to flat design wasn’t just aesthetic—it was a return to Morris’s principle of material honesty. Google’s Material Design took this further, creating a design language that celebrates the unique properties of digital “materials” like light, motion, and layered surfaces.

Form Follows Function became the battle cry of modernist design, but it originated in Arts and Crafts workshops where every decorative element had to earn its place through utility. Today’s best digital products embody this principle through progressive disclosure, showing users only what they need when they need it.

Handcrafted Quality might seem impossible in an age of billion-user platforms, but the principle lives on in microinteractions—those tiny animations and feedback moments that make digital products feel alive and responsive. The subtle bounce when you reach the end of a social media feed, the gentle haptic feedback of an iPhone keyboard or an Apple Watch, the smooth transitions in a well-designed app—these are the digital equivalent of a craftsman’s attention to joinery and finish.

Democratic Design was Morris’s vision of beautiful, functional objects accessible to everyone, not just the wealthy. This translates directly to inclusive design practices, universal accessibility standards, and the open-source movement that has democratized both design tools and knowledge.

Digital Craftsmanship in Practice

Consider Apple’s design evolution under Jony Ive, who explicitly connected his work to Arts and Crafts principles. Ive often spoke about “honest” design—removing unnecessary elements, celebrating the essential function of each component. The original iPhone’s interface wasn’t just minimal; it was truthful about what a digital interface could be.

37 Signal’s approach to software design offers another compelling example. Their “Getting Real” philosophy echoes Morris’s rejection of unnecessary ornamentation. Every feature must justify its existence through user value, not feature-list bragging rights. Their interfaces feel handcrafted in a world of bloated enterprise software, prioritizing clarity and function over impressive complexity.

Even companies outside traditional tech embrace these principles. Patagonia’s digital presence reflects their environmental values through clean, purposeful design that never distracts from their mission. Their website’s honest photography, straightforward navigation, and focus on product utility over flash selling perfectly embodies Arts and Crafts values in digital form.

The Modern Workshop

Today’s design systems function as digital craft guilds, establishing standards and sharing knowledge across teams. Companies like Airbnb, Shopify, and IBM have created comprehensive design systems that ensure quality and consistency at scale—the digital equivalent of Morris’s ideal workshop where skilled craftspeople maintained high standards while collaborating on larger projects.

The rise of the Brad Frost’s atomic design methodology mirrors Arts and Crafts construction principles, building complex interfaces from fundamental, well-crafted components. Just as Morris advocated understanding materials from their basic properties up, atomic design starts with the smallest interface elements and builds systematically toward complete experiences.

Challenges in the Digital Age

The Arts and Crafts influence isn’t without complications. The movement’s emphasis on simplicity can lead to over-simplification that removes necessary complexity. When minimalism becomes dogma, designers risk creating interfaces that are beautiful but unusable, elegant but incomplete.

The tension between craft quality and business scale remains as relevant today as it was in Morris’s time. How do you maintain handcrafted attention to detail when shipping features to millions of users on aggressive timelines? How do you balance the ideal of democratic design with the reality that simpler interfaces often require more sophisticated (and expensive) development?

There’s also the risk of aesthetic elitism disguised as democratic design. When “clean” design becomes a luxury signal, when minimalism excludes users who need more explicit guidance, the movement’s egalitarian ideals get lost in pursuit of design awards.

Looking Forward

As artificial intelligence increasingly assists in design creation, the Arts and Crafts emphasis on human craft becomes more, not less, relevant. The question isn’t whether machines can create functional interfaces—they’re already doing that. The question is whether they can create interfaces that feel genuinely crafted, that show evidence of human consideration and care.

The movement’s environmental consciousness also resonates in an age of digital sustainability. Just as Morris advocated for durable, repairable furniture over disposable fashion, modern designers are considering the environmental impact of digital products—efficient code, long-lasting design systems, and interfaces that don’t require constant updates to remain functional.

The Craft Mindset

For today’s digital designers, embracing Arts and Crafts principles means more than aesthetic choices. It’s about approaching each project with a craftsperson’s mindset: understanding your materials (code, interaction patterns, user contexts), respecting your users’ needs over your ego, and taking pride in work that will outlast current trends.

It means asking Morris’s fundamental questions: Is this useful? Is this beautiful? Does this serve human needs or merely business metrics? Does this design democratize access or create new barriers?

The Arts and Crafts movement failed in its immediate goal of reforming industrial production, but it succeeded in establishing principles that transcend specific technologies or materials. In our age of digital transformation, these principles offer a humanistic framework for creating technology that serves people rather than exploiting them.

When you next encounter a beautifully simple interface, a thoughtfully crafted interaction, or a design system that prioritizes user needs over feature bloat, you’re experiencing the digital descendants of a 19th-century movement that dared to imagine technology in service of human flourishing. William Morris would be proud—and probably amazed—to see his workshop principles scaled to touch billions of lives through the devices in our pockets.

The pixels may be new, but the principles are eternal: truth, beauty, function, and access for all. In bridging the gap between medieval craft traditions and digital futures, the Arts and Crafts movement reminds us that good design is ultimately about human values, not technological capabilities.

As we face new challenges in AI-assisted design and global digital platforms, these 140-year-old principles offer more than historical curiosity—they provide a moral framework for building technology that enhances rather than diminishes human dignity. In the end, that may be the movement’s greatest legacy: proving that the best innovations honor the past while embracing the future.